Jonathan Toniolo • • 9 min read

The Medical Gaze: Why Depression Should Not Be Reduced To Chemical Imbalance

I’ve been battling depression off and on since adolescence.

A few months prior to getting clinically diagnosed, my mental state was especially catatonic.

Some days, concentrating on anything other than food and sleep required a will so great, even the resolve of Sisyphus seemed trivial in comparison.

I tried some non-psychiatric recommendations — talk-therapy, more exercise, dietary changes, herbal remedies — though I couldn’t sense immediate results and, given my lack of will, quickly abandoned them.

My parents had learned about SSRIs after seeing a few of those absolutely scintillating antidepressant commercials — you know, the ones where they casually narrate a number of potential side effects over someone’s glossy smile — and, in a desperate and loving attempt to heal their sick child, finally convinced me to consult a psychiatrist.

When I met with the doctor, we¹ ended up talking about symptoms of depression for the majority of our session (he had been suffering from depression for many years as well). We briefly discussed a few common causes, such as loss, failure, rejection, isolation, and genetic influences, among others.

Although, rather predictably, the conversation eventually segued into a treatment plan based entirely on the physiology of depression; one that suggested my brain chemistry was simply out of balance and that Zoloft was my golden ticket to get it back to “normal.”

The logic seemed to be: “[Insert irrelevant cause] disrupted your normal production levels of serotonin and dopamine, so take this pill to readjust those levels, and you will be healed. ”

In a way, this was reassuring. It relieved some of the burden of responsibility for feeling so miserable — “It’s just my shitty chemistry! There’s nothing I can really do about that…”

I also trusted the doctor knew best and was acting in good faith — especially considering he had also suffered from depression.

The Medical Gaze

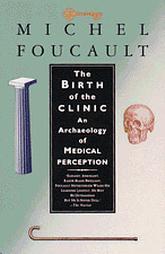

At the time, though, not only did I have little knowledge of the financial incentives for prescribing antidepressants (which, to be fair, didn’t seem like a probable factor in this case), I was also unaware of the dominant medical framework his prescription was based on: the “medical gaze”, as French philosopher Michel Foucault called it.

In his book, The Birth of a Clinic, Foucault talks about this gaze as arising out of the professionalization of the doctor in the early 19th century. In the process of creating a standard biomedical model, he claims these doctors adopted a dehumanizing attitude, one that looked at a patient simply as a set of either healthy or faulty organs.

Medical anthropologist Tess Han writes:

This ‘medical gaze’ is a taught, learned, and institutionalized way of looking and making sense of the body by doctors around the world. It doesn’t take into consideration the patient’s sociological context because doctors are reframing patients as merely another file or case to look at.

Under this gaze, the depressed person is seen as a malfunctioning brain, not someone to be considered as a whole entity. “Disorders became localized to a distinct point within the body” Foucault writes, “dismembered and separated from the rest.”

The medical gaze has its benefits, to be sure. It allows doctors to arrive at a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the patient on the biological level. Things like diagnosing cancer and performing surgery are some of many medical areas that have benefited greatly from this gaze.

However, Foucault argues that there are important variables (emotional and mental states, sociological context, etc.) contributing to illness that are inherently beyond the scope of the medical gaze. Therefore, it’s important that doctors have adequate training in the humanities, especially doctors who will be diagnosing and treating mental illness.²

What My Psychiatrist Ignored

“It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” — Jiddu Krishnamurti

Antidepressants, in my experience, were mostly a palliative solution; one of many defences I used to temporarily cover up more pressing issues. It was like putting daily Band-Aids over a mental gash that kept rotting from underneath; getting me through the day, but with a narrowing awareness. Renegade psychiatrist Kelly Brogan says:

We are prescribed to suppress and eliminate signs that are actually meaningful messages about our state of dis-ease. We don’t ask “why”, we don’t look to the roots of these symptoms. We just want to get back to work. To feel “normal.”

Looking back, I see that some of those pressing issues were various social and political realities: hyper-consumerism, different forms of repression, environmental catastrophe, poverty, injustice, greed, etc.

It’s especially telling that even though my personal life may have been great by all objective measures — I had friends, girlfriends, loving parents, and (generally speaking) a promising future — I couldn’t shake the melancholic feeling these realities produced.

I felt something was fundamentally sick about our society, and this feeling would often drain my motivation to actively participate in it.

At the time, I didn’t understand this as a sign that I genuinely cared about improving society.

By taking regimented medication, this truth became a distant blur, hidden from my awareness. My focus changed entirely. I became consumed with maintaining my personal “bubble of psychology”.

And I became more depressed.

After much reflection, it’s become all too apparent that the way I should’ve addressed depression, in this case³, was not through a medicated suppression of symptoms, nor any kind of redirected focus of attention, but rather by engaging with its triggers. What I needed was political awareness. And insofar as certain modulations in neurochemistry could help me realize this, they would’ve been useful.

Author Charles Eisenstein reflects this experience of depression in his article Mutiny of the Soul, Revisited:

Depression, ADHD, anxiety, etc. aren’t chemical malfunctions of the brain, nor spiritual malfunctions of the mind; rather, they are forms of legitimate rebellion against life structures that are unworthy of one’s full participation or attention.

This is certainly not to say we should neglect the personal dimensions of depression — such as poor life habits, past traumas, limiting beliefs, lack of self-love/self-expression etc. These are prevalent and important causes to address as well. But, as Eisenstein suggests, depression often has a major sociological component that’s been widely ignored.

In his article, Why Therapists Should Talk Politics, psychotherapist Richard Brouillette summarizes my sentiment:

Should therapy strive to help a patient adjust, or to help prepare him to change the world around him? Is the patient’s internal world skewed? Or is it the so-called real world that has gone awry? Usually, it’s some combination of the two, and a good psychotherapist, I think, will help the patient navigate between those two extremes.

The Role of Culture

Cultural influences are constantly affecting how we think and feel. Although it’s difficult to escape this — even counter-culture is still culture — the significance of these influences tends to vary from person to person, depending on their level of personal integrity.

But at times when we find ourselves plagued by depression and desperate for healing, our integrity is inherently fragile. We become both psychologically and emotionally vulnerable, and the gravity of these influences becomes all the more potent.

At best, our culture contains influences that are nurturing and supportive in these moments, gracefully guiding us through the more challenging aspects of depression. We’re acknowledged as whole entities, embedded in a web of complex relationships to the outside world.

More often than not, though, we’re woefully misguided. We’re instructed to suppress important signals and intuitions, making us feel powerless. We’re prescribed medications that rarely help us to process underlying causes. Depression gets reduced to genetic flaws or chemical imbalances, neither of which reflect our true sense of agency in the matter.

Interestingly, there are some important political implications to the latter reductionistic approach4. For example, it suggests that there’s nothing we need to question beyond our biological deficiencies. Focus on your bad chemistry. The outside world is fine. Don’t question the existing social order; just run along now and regulate those neurotransmitters.

There’s also a certain naivete that underlies this approach; one that implies that the external world has little to no influence on us; that our feelings and thoughts are largely independent of our environments. We are atomized entities, as are the illnesses that plague us.

But this is true only to the degree that we let ourselves feel it’s true. As the late Alan Watts put it, “We try to pretend, you see, that the external world exists altogether independently of us.”

We only put up boundaries around our sense of self to the degree that we find our environments threatening or harmful. And as we begin to sense how interconnected we are with our environments, the more we’ll see how these environments affect our well-being.

Consider this statement from Dave Chappelle:

“It is sometimes an appropriate response to reality to go insane.”

— Philip K. Dick

I think oftentimes when we dismiss someone as “crazy” (not in the “Dave is so quirky” sense, but actually referring to a mental illness), we’re unconsciously projecting the insecurities of our own sanity. These “crazy” individuals trigger a part of us that’s terrified of collapsing; the tenuousness of “keeping it together”.

But insofar as we’ve confronted this fear in ourselves, we can begin to understand and look at “craziness” more compassionately. We gain the patience and composure to ask more meaningful questions:

Has this person been isolated for much too long?

Have they been engulfed by overwhelming fear or danger?

Are they undergoing a process of transformation?

Is their environment sick?

Or are they even “crazy” at all? Perhaps their behavior just doesn’t align with our society’s arbitrary standard of normality — people from other cultures surely reflect this difference, just as we most certainly do to them. Perhaps its something deeper altogether.

Of course, these questions may prove to be irrelevant in some cases — especially if our personal safety is at risk. But as a kind of cultural protocol, they allow for vital considerations to be unearthed, the kinds that are all too often buried beneath knee-jerk avoidance tactics or reductionistic labels. At the very least, they help not to exacerbate symptoms, seeing that social stigma is a major factor in worsening symptoms.

A Holistic View of Depression

My psychiatrist wasn’t wrong in saying that my brain chemistry was “off” — something was clearly off or I wouldn’t have been there in the first place. What I find troubling, though, is how that ended up being the primary locus of treatment. Physician and drug addiction expert Gabor Mate says:

The dominant medical tendency in the past few decades has been to reduce mental illness to chemical imbalances in the brain — for example, a deficiency of the chemical messenger serotonin. The obvious solution is a drug to increase serotonin levels. Such biochemical explanations are dangerous oversimplifications. The level, balance and activity of serotonin and other brain chemicals are, throughout a person’s lifetime, affected by emotional stresses. Whether in our jobs or in our personal relationships, our interactions with the environment do much to determine our brain’s chemistry.

Depression, like many other mental illnesses, is multi-dimensional. And if we are to properly address the condition, we need to explore the causal factors more broadly — audit our society’s laws and policies, the institutions we’re a part of; reexamine our work and home spaces, our social circles and interpersonal relationships, the health of our ecological environments; even the architecture that surrounds us has been said to affect our moods.

Eisenstein writes:

The “whole of one’s life” extends to include that person’s relationships to others and to society. If we are to take Krishnamurti at his word, then this epidemic calls for therapies that are social, economic, and political, and not just physical or even mental. In other words, there is a political dimension to the epidemic of psychiatric illnesses.

This shouldn’t come off as a call to flush our medications down the toilet, either. Antidepressants and other psychopharmaceuticals have brought a useful kind of relative stability to many people’s lives (albeit limited — given a dose of heroin, even the homeless could begin to see their situation favorably).

But relative stability is tenuous. Depression is always lurking underneath. We should be wary of this brand of stability or too much comfort, for they can often silence our questioning impulses, rendering very real issues as meaningless.

For those of us whose depression has been treatment resistant for most of our lives, I’m suggesting we consider this:

Our persisting symptoms may be indicative of a sickness beyond a localized pathology.

After many years of digging into my own depression, I’ve become all too familiar with the pain and confusion that comes with turning ourselves inside out, from engaging those “why” questions more honestly and broadly and for longer periods of time, from questioning our sociological context and its influence on our lives. No doubt about it: this process is uncomfortable and trying.

Yet, I think these difficult inquiries have ultimately done what medication could not do: addressed the root causes of my discontent. In coming to a broader understanding of my depression, I’ve restored the will to engage life fully again; a will that’s now powerfully sustained by taking back the responsibility for healing.

As Eisenstein notes, “To be well in a profoundly sick society, one must contribute to the healing of that society.”

Footnotes:

1. Any usage of “we” “us” “our” or “I’ is referring to those of us living within the United States, but other societies may of course be implied.

2. There seems to be a growing number of mental health professionals adopting George Engels’ biopsychosocial model to understand and treat mental illness, which is encouraging.

3. Some might distinguish this as demoralization.

4. What Foucault would call “biopower“.

Further Study: The Birth of a Clinic by Michel Foucault

Disclaimer: We at HighExistence acknowledge that many people need and genuinely benefit from medications that treat mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, etc. This article is not meant to offend those who need medication or to encourage anyone to brashly cease the use of medication. Rather, it is intended to demonstrate that environmental factors play a larger role in mental disorders than is commonly assumed. This article is not a substitute for professional help. Please be responsible and take care.

![Seneca’s Groundless Fears: 11 Stoic Principles for Overcoming Panic [Video]](/content/images/size/w600/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/seneca.png)