Ronan Loughney • • 19 min read

How to Deal With Your Inner Critic

9 Steps For Turning Your Inner Critic Into an Inner Ally

Last month, I decided to embark on a 30X challenge, where I would investigate my own Inner Critic for thirty days, using established techniques and resources, and discovering some of my own along the way. This article is a deep dive into my experience of significantly healing my internal world. If you are struggling with your Inner Critic, you can follow these steps and the Inner Critic Exercises (Section 5 below) for you to follow and repair your relationship with yourself.

We live in a time of intense pressure on the individual. Society importunes us to live our best life, to know what we want and pursue it with single-minded determination. Mental health awareness has improved, but it is still associated with the ‘mentally ill’, the pathologised. Yet so many of us are suffering. We find ourselves falling short of society’s standards, such that, not only are many of us failing to live our best lives, we are failing to live a life we treasure much at all.

The irony here is that through our distraction before the gaudy lights of our materialist, attention-hijacking culture, we fail to see how much of our dissatisfaction is endogenously caused. (This is not to say that we are not complex entities influenced and constituted by our environment as pointed out in books like the excellent Lost Connections. However, fundamentally, empowerment must arise from taking a certain level of ownership over our thoughts and emotions). Such is our distraction that for many of us, our internal landscapes are unmapped, untended, and are simply whatever occurs in the space between the next dopamine jolt.

Today’s ‘bizarre normal’ is one where thoughts are left to run wild around the unguarded caverns of our psyche as we search outside for what will quell the sense of unease and dissatisfaction. We realise that there is a problem, but misunderstand not only what it is but where it is.

Here is a nine-stage process I developed for healing the neglected parts of myself. Many of the ideas came from Dr Aziz Gazipura's On My Own Side, which is an excellent additional resource.

1. CONTEXTUALISE THE INNER CRITIC

Personally, I’ve always had a problematic relationship with myself. The fact that such a sentence is even coherent, let alone that it will be familiar to many of you, is surprising when you think about it.

How is it that we can have a problematic relationship with ourselves? Are we somehow divided? And if so, is this division naturally antagonistic? Are we perhaps several people, bundled into a body, all vying for competition?

The first issue comes, I would say, precisely from there being a lack of clarity around these kinds of questions. We are aware of having negative thoughts which do not serve us, but these thoughts are regarded vaguely as a kind of extension of a unilateral personality and, by inference, as an unalterable and innate feature of our inner lives and selves.

One of the most critical steps therefore (even the basis from which all others lead), is putting these negative thoughts in their proper context. That is, understanding that we are not equivalent to our thoughts, and that they, in fact, could be said to have a mind of their own.

This can be achieved through basic mindfulness techniques. Or, for anyone to whom that term sounds off-putting for whatever reason, simply through taking a step back the next time you notice yourself having negative thoughts and trying to observe rather than engage with them.

Even if you get sucked into thought immediately, the initial recognition of the fact that you can observe these thoughts at all is enough to show you that you are not the same as them. Once you do this, you can gain some emotional distance, and see your thoughts for what they really are (i.e. phenomena arising and passing, rather than some permanent feature of whatever makes up ‘you’).

When we acknowledge our thoughts as something occurring within us, rather than constituting us, we begin to understand that we often tolerate a manner of self-talk which we never would if it came from some other person. (Especially when I am hungover, my self-talk can become so lacerating as to be abusive.) This indicates, if nothing else, that there is something amiss in how we are relating to ourselves, and serves as a motivation for changing this relationship.

2. IDENTIFY THE INNER CRITIC

At this point, we might want to ask, ‘What is the Inner Critic?’, ‘Who is this voice lurking in my head, hurling insults at me?’, 'What is its nature?'

The Inner Critic can be viewed as a composite of and abstraction from all of the perceived criticism that we have faced in life to date. This can be actual criticism received (e.g. when you were told off for breaking the rules as a child) or implicit criticism (e.g. not receiving praise equivalent to our expectations from our parents, then internalised as, ‘I am not good enough’.)

This voice is an extrapolation from these experiences, asking, ‘What do they tell me about my personal value and about how I should navigate the world in order to increase this value (and minimise criticism) going forward?’

Because it is a composite of real and imagined criticisms from all sorts of different sources, attributed with significance according to the child’s still-developing concept of social hierarchies and personal values, the self-critic is by nature an internally contradictory, unreasonable and unrealistically harsh judge.

Moreover, its demands are outdated, since what we want is likely to have shifted radically from when we were a child (when the foundations for this voice were established). Back then, security and social approbation would have been much higher up the list because we had not discovered or were not seeking to discover our own character or manifest our deepest purpose yet.

The Inner Critic is not all bad though. It can have value in reminding us of social norms and expectations, which we can use to navigate the complexities of social existence. As we will see later, what this means is that it is our relationship to it which makes it good or bad. Not the inner critic itself.

Here's old Sigmund after a particularly brain-curdling analytic session

The Inner Critic can be seen as overlapping heavily with Freud’s Super Ego - the innate sense each of us has of familial, social and even moral values and therefore what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. This is an important similiarity, because Freudian Psychology holds that in order to be psychologically healthy, we must integrate the Super Ego into our psyche. We become psychologically unhealthy when we subordinate our own sense of right and wrong entirely to the Super Ego. But we should still listen to it. It's just that then we should make our own judgement. (We'll look at this more going forward).

To be clear then, it is not that we are being wantonly attacked by our Inner Critic. Rather, as we begin to understand it, we see that it has our best interests at heart. It simply has a biased or mistaken view of what constitutes ‘our’ interests. Through rigorously scanning our environment for social cues, it is attempting to regulate our behaviour in order to protect us.

This is a key realisation: your Inner Critic is in fact a friend, albeit one in disguise.

3. APPROACH THE INNER CRITIC WITH LOVE

Once we have established what the Inner Critic actually is, the next step is to begin characterising this voice. This allows us to recognise when it is talking and helps to make the matter of relating with it as vivid, and thereby as accessible, as possible. (Although it derives from disparate memories and stimuli, because it is our mind’s composite abstraction from those memories and stimuli, it takes on an identifiable voice and character).

Far from revealing the dragon that one must now do battle with, in my experience, this investigation reveals the insubstantiality and immaturity of the Inner Critic. It is as Rilke said:

“Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.”

Why so serious Rainer? They're only princesses!

Because what is interesting is that, when the Inner Critic is approached with this genuine curiosity, with the desire to get to know it and really heal its pain, it begins to become shy. Like the toddler who screams for attention and then blanches when it is given, knowing it has no basis for its outburst, the Inner Critic will shuffle its feet in embarrassment when you really ask it what is the matter, with kindness and patience.

This can seem dismissive of those who have experienced deep and aggressive psychological trauma at the hands of others. If you have been abused physically or sexually for example, this will surely constitute a significant part of your Inner Critic, rendering it far more aggressive and frightening than my own.

I cannot comment much on the potential experience for those with such a form of Inner Critic. However, I would repeat that the critic is not equivalent to the people and events that generated it. It is the residue of those experiences, which your mind now uses against itself in intended self-protection. Its insubstantiality, the fact that it is a scared and wounded part of you, which you can investigate (and heal) with love, remains regardless of such origins.

Of course, because of the potentially overwhelming nature of an Inner Critic which comes in the form of an oppressor or abuser, it is essential to complement these investigations with a mindfulness practice that can help you gain distance from your thoughts, as well as a Metta (Loving-kindness) practice which can support you in generating feelings of love and compassion for yourself.

If you have any worries, it is recommended that you engage the Inner Critic when you are somewhere that you feel safe, ensuring there are supportive people on hand or contactable who are aware you are engaging in this work. Ultimately, only you can judge whether you feel safe enough to begin your investigation.

In any case, the point of this step - Approach With Love - is to acknowledge that the Inner Critic is emotional and not logical. Rationalising your negative emotions has its place, but must be informed first and foremost by love and sympathy.

4. NAME THE INNER CRITIC

As you get to know your Inner Critic, it can be helpful to name and characterise it. This not only allows you to contextualise and identify it - ‘oh, it’s them again’ - but is a great opportunity to bring some levity to the situation.

My Inner Critic is called Nigel and he talks as if someone is squeezing his nose. This is a fairly children’s TV way of making myself laugh, but I do have a little chuckle to myself each time I check in saying, ‘Alright Nigel you old bastard, you seem very upset about the fact that no one laughed at your slightly off-colour joke. Tell me all about it,’ (before letting his pernickety little diatribe spool out until it exhausts itself).

Gollum was Smeagol's pretty brutal inner critic. He could have done with these 10 steps! (Image from here)

This combination of humorous characterisation and a loving approach fundamentally alters the relationship that you have with the Inner Critic. You are the one in charge, which does not mean that you then start bossing it around. Rather, you can now break the negative chain of harsh self-talk by soothing it.

Rather than cowering meekly as our dark side berates us, we suddenly realise that the relationship should be the other way around. We see that where we were looking for support from a scared and wounded part of ourselves, it is in fact this stable, calm, loving, pro-active observer within us which is responsible for us and able to give us support.

Shirzad Chamine, Stanford Psychologist and author of the ‘Positive Intelligence programme’, refers to this voice as the Sage, as opposed to the Saboteur (the negative part of our psyche that encompasses the Inner Critic). He characterises psychological health as a mind in which the Sage speaks more frequently and loudly than the Saboteur/Inner Critic, which is a helpfully simple way of looking at it.

5. TALK TO THE INNER CRITIC

This section is all about Inner Critic Exercises. Fundamentally the real shift begins when we work with the Inner Critic over time.

As with all internal phenomena, it is not about silencing any part of ourselves. It is about becoming ok with it, which in turn, paradoxically, quietens it. The only way out is through.

Again paradoxically, although the first step is to contextualise the voice as separate from oneself, the ultimate aim is to integrate the parts of ourselves we normally push away into one coherent self. We gain distance from the suffocating voices to hear them more clearly, and then we welcome them back in as friends. You are trying to reduce the dissonance inside by increasing your identification with the part of you is looking out for the wellbeing of the whole.

So, we externalise the voice, we identify it as in need of our support, we investigate with love and curiosity, characterise and accept it. But how does this process actually work?

Talking to oneself is presented to us in films as insanity 101. Hearing voices, developing multiple personalities etc. But the fact is, you are already talking to yourself. It's just that that process has been unreflective and undeliberate to date. It's about being intentional in the process that is already approaching.

As it is essentially a matter of relationship, the manner in which we approach our Inner Critic is much like coaching or talking therapy. That is, it is about checking in and asking open questions in order to bring to light what has been pushed into the shadows (and thereby taken on a form far scarier than it really possesses).

Ken Wilber came up with many effective techniques for how to relate better to ourselves. (Image from here.)

In the absence of a therapist, you can do this thorough simply posing questions to yourself by whatever means work for you:

- Through conversational journaling, engaging in a dialogue between your Inner Critic and your Sage or Higher self, which can help to gather racing or messy thoughts;

- Through CBT, especially the Triple Column Technique, or Stoic frame control exercises, which can help uncover distortions in your thought process.

- Through setting up two chairs and embodying the Inner Critic talking to you in a makeshift Gollum/Smeagol pastiche, which can help make the thoughts more real and thus easier to work with.

- Through asking a friend to read out the criticisms your Inner Critic makes and then replying with patience and compassion, or embodying the Inner Critic yourself and having the friend respond compassionately to you. The key to remember, however you do it, is that you hold the answers, because the Inner Critic is within you. And you are in charge. You choose the manner of the relationship. (These kinds of ‘speaking to your different parts’ practices have a broader psychological application, in Ken Wilber’s Transpersonal Psychology for example).

- Through dropping into your body: when you notice the Inner Critic, where do you feel it in your body? What kind of sensation is it? I, for example, experience shame as a constriction around the forehead and nose, almost as if I am flinching under the gaze of the world. Simply noticing the somatic basis of my feelings allows me to look at them objectively and create a difference between them and ‘me’.

Again, it is important to bear in mind that for some of us, engaging with these buried emotions will have a potentially overwhelming effect. We may even have a non-cognitive bodily reaction. The above precautionary steps regarding establishing a safe environment and having people on hand are especially important with these deeper practices.

As a writer, conversational journaling works best for me. Here is a worked example:

‘All right Nigel, you loveable little sulk, what’s up this time?’

‘I am a fat shit who shouldn’t eat so much, especially without exercising. I shouldn’t have slept in so late either. I should have achieved more today. I’m a mess.’

‘Oh’, you say, trying not to condescend towards such a sensitive little creature. ‘Tell me more’.

‘I never work towards achieving my dreams’, he replies back a little more sheepishly.

‘Really. Never?’, you nudge. (Nigel likes to be dramatic).

‘Well, maybe not “‘never.’ But not so much as I would like’.

‘I see. Would you say that makes you a - and I’ll use your words here - ‘fat shit’?’

‘No. I suppose I just have an idealised image in my head of what I should look like which I’m using as a stick to beat myself with. I’m not always lazy and, in fact, I’m just noticing this because it’s an exception’.

‘That’s better, Nige. What should we do about it then?’

‘Try again tomorrow. And I’ll try to be less harsh on myself next time’.

Whether this resonates with you or not, what we see here is an example of the Inner Critic reflecting society’s destructively unrealistic expectations. More importantly, we see its tendency to extrapolate total self-worth through the perceived worthiness of an action or set of actions. It is this process which must be challenged.

The aim is that, rather than deriving our value from unrealistic expectations that never exhaust themselves, we instead find our inherent value through our Higher Self or Sage, the part of us which is naturally optimistic, stable and encouraging.

6. LEARN FROM THE INNER CRITIC

What we also notice is that we can work with the Inner Critic to take proactive action. As we have seen, it is not simply a voice that we have to lead gently towards realising its own error. Remember, the Inner Critic wants what is best for you, which at times overlaps with what is socially acceptable (e.g. adherence to social norms helps us maintain relationships as well as an essential level of order and stability in our lives.)

That is to say, our own values are co-mingled with society’s. They do not occur in a vacuum. Values are the principles we establish around how we think a person should act in the world. As a person, you are an innately social being, embedded in networks and constituted by the tastes, opinions and biases of those around you.

When the Inner Critic complains that you are out of step with a given value, it is asking you: ‘Is this value your own?’ and, ‘Do you want it to be?’ As such, it is a mirror you hold up to yourself in order to check that you are an integral whole, not merely a confused battleground of internal and external values.

So sometimes that nagging voice is good. Like pain, it is the sign that something is amiss and needs to be addressed. It can be helpful to ask the Inner Critic what it would take to make it feel better, resolve to follow its instructions, and thank it for its concern.

For example, I realised through speaking to my Inner Critic that I was not pulling my weight in the shared accommodation I was staying in and that I should do more chores. I started doing them and immediately felt better. Great! Thank you Inner Critic! Moreover, such a respectful and mutually communicative attitude only goes further to improving your internal relationship and increasing your integrity.

Again, this is not about trying to escape guilt and all negative feelings, which is impossible. It is about embracing them, listening (but stopping at rumination), and deciding whether the Inner Critic’s demands are actionable or not. Again, simply by listening and approaching it openly, negative feelings will diminish and positive ones will increase naturally.

7. KNOW WHAT YOU WANT

Having offered this caveat, it is important to remember that most of the time, especially in the era of social media, we are far too socially preoccupied. To simplify Abraham Lincoln’s famous phrase, ‘You can’t please all of the people all of the time’, which is what your Inner Critic wants to do.

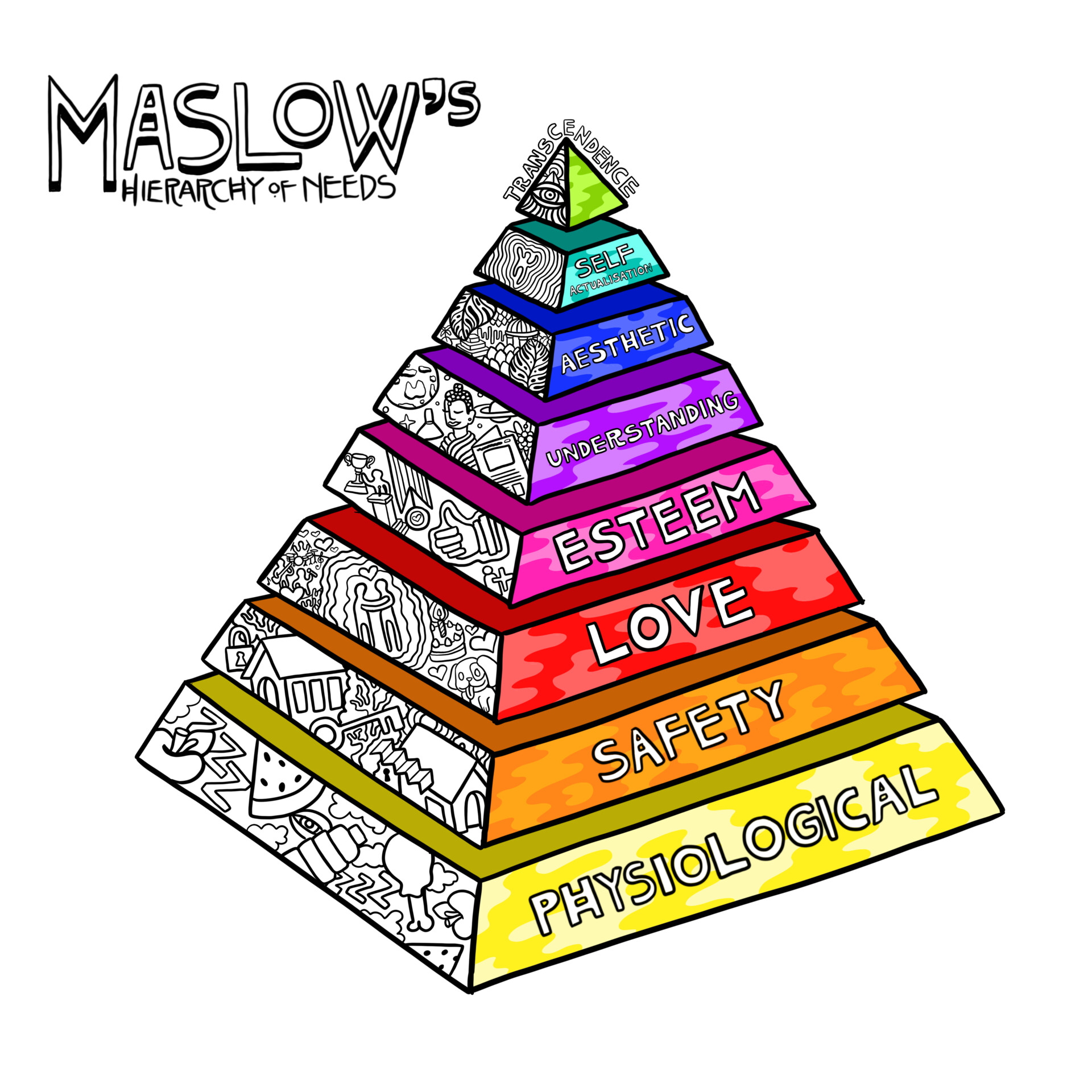

Because we cannot please all of the people all of the time, and we actually cannot really guarantee who we might end up pissing off accidentally at any given time, we begin to realise that the most important thing is knowing what it is we ourselves want. This is incredibly difficult (Maslow believed it was one of the rarest psychological achievements) and is a lifelong task, requiring iteration and refinement. But without knowing what we want, we are doomed to work against our own self-interests and all of the attendant internal friction and pain that generates.

Really knowing what we want comes right near the top of the pyramid. But there's nothing more meaningful than making the journey. (Image from here).

This is absolutely not to say to act selfishly, since what we want here is not to be confused with mere passing whims or desires. Our deepest wants and values, as we have seen, include the world around us. And being intimately and deeply connected with them is a necessary compass for taking action in a world that is too complex to consult and ask for permission each and every time we interact with it.

8. ACT WITH INTEGRITY

Once this process is done, and we are clear on what it is we want and what actions we must take to get there, the difficult work begins. To act in accordance with these aims.

The idea is to make our actions as intentional as possible, so that before acting, we know why it is we are doing what we are doing, and thus back ourselves before, during and after taking action. We thus become more free from anxiety about outcomes, because we know that we have acted with integrity and done our best to act in a way that we think is right.

TIP:

It is helpful to remind yourself of your values before entering situations when the Inner Critic is likely to emerge. I often berate myself in group situations for talking too much, for example, and yet I also believe in the value of vulnerability and sharing, and that by sharing we can help others in turn share.

Before a social gathering, I remind myself of this value, and check in again before I am about to share: Why am I doing this?

If my answer is honestly to facilitate the sharing of others, to smooth the interactions of the group as a whole, I share anyway. Thus, when the Inner Critic inevitably rears its head because something didn’t go exactly as I had planned, its words are empty, because there is simply nothing else I would have done if the situation arose again.

One is freed of the burden of regrets (which are a means by which the Inner Critic unhelpfully manifests itself), but can still learn from and reflect on experience, having created an internal space free of shame where one can really hear.

Above all, engaging with the Inner Critic, whether heeding its warnings, soothing it, or politely ignoring its complaints, is about learning and growth. Humans need to grow. If we don’t, we stagnate, becoming complacent and depressed.

Life is forever growing more complex, pushing its own boundaries, and we are at our best when engaging in this form of self-transcendence, breaking beyond ourselves. The Inner Critic is your ally in this, your little alarm bell which questions you when you are not being the best version of yourself. It’s just that you can decide whether it is right or not.

9. GET REST AND RECUPERATION

You have to give the mind pixies time to clean your brain out while you rest. (Image from here).

Before finishing, we should bear in mind the delicate connection between heeding the Inner Critic’s calls to grow and allowing ourselves rest and recuperation.

Ironically, by being too attentive to the part of us that wants what is best for us - challenge and growth - we can turn our lives into a never-ending slog where we are constantly in a state of stress and semi-exhaustion.

For this, it is necessary to understand that, as with the seasons, all growth occurs in cycles. There are times when we must strive and break through ourselves, and times when we must rest, recuperate, and gather ourselves in. Which means that rewarding ourselves is just as important as pushing ourselves. We should praise ourselves for our achievements, for listening to ourselves, for working towards our goals. If the Inner Critic pipes up at times of rest and relaxation we should still listen, but remind it in no uncertain terms that its work, for now, is done.

—————————-

‘The mind is a terrible master, but an excellent servant’ (anon).

After spending a month checking in with myself for no more than ten minutes a day, I made progress I wouldn't have thought possible. Just by facing the problem rather than turning away from it, suddenly something which had dogged me my entire life seemed not only manageable, but quite insubstantial.

This has altered my relationship to my Inner Critic, but also how I approach other formerly daunting and unconquerable aspects of my inner world. Not only do I now have the self-belief that it is possible to heal these elements, but since the above can pertain to any manner of self-enquiry, I also have a roadmap for confronting and ultimately integrating any and all aspects of myself that I have pushed away.

Months later, I began to be beset by feelings of shame. It was as if my initial process of self-inquiry cleared up the most surface levels of inner conflict, leading the deeper, more twisted aspects of my Inner Critic to retreat, only to come back later with renewed vigour having been attacked.

I initially felt defeated by this, thinking I had dealt with the negative aspects of my Inner Critic, that I had won. But of course, this is a lifelong process. As implied in Step 10, this work will go in waves. It is something we must be prepared to return to repeatedly, knowing we go a little further and become a little more strong and whole each time.

So whenever you notice sadness, anger, fear, or any emotion you would like to push away, try opening yourself out to it, and seeing if you can heal its pain through the steps above. It is my belief and hope that, the more each of us heals these wounded parts of ourselves, the more we help to heal those parts of others in turn.

To take the 30X challenge yourself, simply commit to investigating your Inner Critic in the manner described in the ‘Talk to Yourself’ step above, for 30 days, being sure to record how you feel at the start and end of the challenge.

And if you enjoy that challenge, why not try our legendary 30 Challenges to Enlightenment course - a blueprint for upgrading your consciousness and becoming who you want to be.

_________

I would like to thank Jon Brooks, for leading a wonderful workshop and inspiring me to take on this challenge; Eric Brown, for his insistence on the combination of action with thought; Mike Slavin, for showing me that when we feel like a wounded child, it is time to love ourselves as a mother; and Mike Kol Adam, for reminding me that the real aim is to become loving kindness, and we cannot expect to get there all at once.

About Ronan Loughney

I’m a writer, musician, coach and facilitator committed to seeking truth, finding beauty and deepening human connection and community. I believe the meaning of life is in each person coming into a full embodiment of themselves and discovering how to share it with the world around them.

If you liked this article or want to get involved with the course I am putting together about human flourishing and social impact, then please visit www.ronanloughney.com and subscribe or reach out!

Ronan Loughney

Ronan is a trainee-Psychotherapist, MDMA Guide and Coach. You can reach him via www.ronanloughney.com or email him directly at ronanloughney@gmail.com