Jon Brooks • • 13 min read

Reading Hundreds of Self-Improvement Books is a Terrible Idea

I was eighteen years old and had just started film school.

Film students can be weird, myself included.

We think that because we love films, we automatically know how to make great films.

This way of thinking is equivalent to getting hit by Mike Tyson and then concluding you can fight like him.

In my first screenwriting class, I genuinely thought I could write better scripts than my teacher, who was a professional scriptwriter.

It was only after speaking to my cousin, who had also studied filmmaking a few years before me that I started to realize how much I didn’t know.

My cousin started throwing all of these concepts at my young film student mind. Concepts like character conflict, the inciting incident, archplots, miniplots, subplots, and the hero’s journey.

He told me that all of my favorite Hollywood blockbusters followed a specific formula, and I could use this same formula in my own scripts.

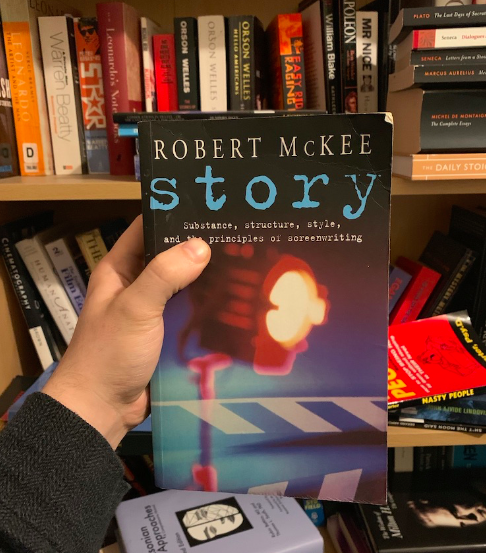

I asked my cousin where he learned this from and he told me about a book he was reading called Story by a screenwriting expert called Robert McKee.

‘Damn, reading about screenwriting, that sounds like a drag,’ I thought.

But as the days progressed, I kept thinking about the conversation I had with my cousin.

If I read this book he was raving about, I would actually know a thing or two about screenwriting instead of merely thinking I know it all due to my egotistical biases.

I bought the book and read it in a few days.

When I re-entered my scriptwriting class, I was transformed.

My classmates immediately started viewing me as “the scriptwriting guy” and gave me authority over them in this area of filmmaking. I sounded like I knew what I was talking about.

From this point on, I saw reading as a superpower.

Reading doesn’t have to make you weak and nerdy. In fact, reading can make you supremely powerful.

Napoleon in his younger years went without food just so he could purchase more books.

Why is reading so useful? You can take a person’s entire life of study—all their failings and successes and in a few days get the best gems of wisdom they have to offer.

As I read more and more books, I wanted to read even more.

My desire for knowledge became insatiable.

I fantasized about the idea of being able to download books into my head like Neo from The Matrix.

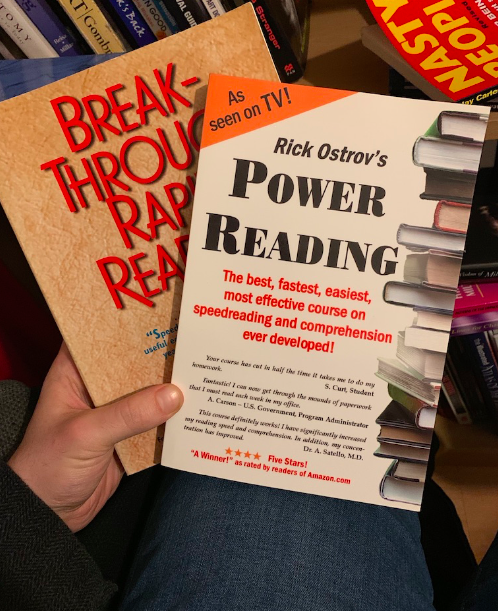

It wasn’t long before I started reading books on… how to read more books faster.

I began practicing speed reading.

I started piling more and more books into my lists.

But while all this was going on, unbeknownst to me there was damage being done.

My relationship to books, to authors, to words, to ideas were changing. They were changing for the worst.

Now, 10 years later, my approach to reading is completely different.

I want to now share with you the things I’ve learned about reading so you don’t make the same mistakes as I did.

Reading Lists

Have you ever discovered a reading list by someone you admire and got all excited?

I have. I remember finding reading lists by Sam Harris, Jordan Peterson, Derren Brown, and Alain de Botton.

Here is my reading sorted for the next decade, I thought.

I do still like reading lists a lot, but I think they should be used with some caution.

Alain de Botton said, ”Most of what makes a book ‘good’ is that we are reading it at the right moment for us.”

Someone else’s reading list might be set up the way it is because in their life those specific books spoke to them based on the experiences they were having around the reading itself.

Our experiences and values determine what makes a book good.

Think of your favorite books. What was going on in your life when you read them? How did you find them?

Even though I kept long lists of “to-reads,” I would often find myself confronted with a problem of some kind, then going off and trying to figure that problem out via books I found organically.

In the last year, most of the best books I’ve read have been titles I had never heard of till a few moments before their purchase.

If you really like a particular thinker and peruse their reading list and pick out something that speaks to you, all the more power to you. But looking through a list of “Books You Must Read Before You Die” is unwise.

In the end, you must create your own reading list—dare to read the books you are drawn to rather than pushed towards.

Viewing Books As a Goal

The other issue that reading lists presents to us is that we start to viewing books as some kind of goal to be “completed.” This perspective could quite easily lead us to rush through a book without truly considering and savoring the authors arguments.

Richard Rodriguez experienced this in his early years:

”I needed to keep looking at the book jacket comments to remind myself what the text was about. Nevertheless,… I looked at every word of the text. And by the time I reached the last word, I convinced myself that I had read The Republic. In a ceremony of great pride, I solemnly crossed Plato off my list.”

What is the value of having read every great book in existence if it doesn’t change us?

Epictetus in his Discourses compares the act of learning to lifting weights:

”It’s as if I were to say to an athlete, ‘Show me your shoulders,’ and he responded with, ‘Have a look at my weights.’ ‘Get out of here with your gigantic weights!’ I’d say, ‘What I want to see isn’t your weights but how you’ve profited from using them.”’

Trying to cram as many books into our “finished reading list” is much like similar to trying to fill our house with as many weights as possible while losing sight of the purpose of having them in the first place.

And following Epictetus’ analogy further, one of them most important parts of lifting weights is recovery—that’s where we grow.

Do we need similar periods of rest with reading to assimilate and integrate our newfound knowledge?

Speedreading

“I’m a slow reader, but I usually get through seventy or eighty books a year, most fiction. I don’t read in order to study the craft; I read because I like to read”

― Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

”I took a speed-reading course and read War and Peace in twenty minutes. It involves Russia.”

—Woody Allen

Wouldn’t it be so amazing if you could read a book a day? How about 4 books a day?

I used to think this way, but now I don’t.

I believe that we can only unlock

Epictetus’s Handbook consists of 54 teachings. This book, which is one of the greatest works of philosophy ever written, can be read in an hour.

The question is, should it be read in one hour?

I see social learning—which is what books are—as being keys that unlock certain portals in lived experience. You learn something, then you go out into the world and project that new understanding onto reality.

It is the combination of time + experience + information that produces transformation and wisdom. For this reason, it would be much more productive to read a few of Epictetus’ teachings each day across a span of time, or to re-read the book multiple times in its entirety close together.

I much prefer Machiavelli’s perspective on reading:

“When evening comes, I return home and go into my study. On the threshold I strip off my muddy, sweaty, workday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the antique courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born. And there I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives of their actions, and they, in their humanity, reply to me. And for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexation, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death: I pass indeed into their world.”

Speedreading for the most part requires that one “reduce subvocalization.” When you read in you head, your throat and vocal chords still activate in a similar but smaller way than if you had said the word out loud.

This is how mentalists are able to read your mind: when you think of a word or picture, your lips and vocal chords make tiny movements which can be lipread by an expert eye.

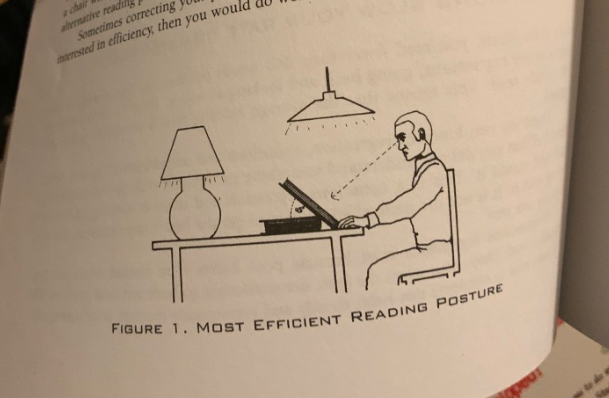

There are many different techniques that comprise speedreading. Some books go into as much detail as to explain the perfect reading angle for your books.

I believe learning to speed read did a lot of damage to my ability to read well.

What you are doing while speedreading is training yourself to skim efficiently. No longer are you soaking in the nuances of the language, the context, the specific tonality of the writer.

The author of the book did not write the book to be read without subvocalization, if he or she had written their book with this aim in mind, they would have written a different book.

Beyond this, speedreading changes your relationship to reading. There is so much focus on efficiency, that you end up seeing books as some kind of rubix cube to solve as quickly as possible—a mere nutrition without taste or experience.

Jordan Peterson described the book Beyond Good and Evil as follows:

“Beyond Good and Evil—to think of it as a book is a really foolish framework. Because this is what a book is when people think about a book:

“It’s like a material entity. It’s eight inches high and six inches wide and two inches thick and weighs a pound, and it’s made out of paper and its between two covers. And that’s the materialist’s a priori sort of axiomatic view of a book. But Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil isn’t a book at all. It’s a series of bombs, and each sentence is a bomb. And each sentence blows things up that people didn’t even know exist.”

Peterson is saying that every sentence is so. How on earth could you speed read a book like this, where every sentence has been so thoroughly thought through.

Reading to Get Wiser

“The art of living is more like wrestling than dancing, in so far as it stands ready against the accidental and the unforeseen, and is not apt to fall.”

— Marcus Aurelius

When I started studying Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, my entire understanding of learning changed.

Thanks to the internet and easy access to recording equipment, we can share ideas faster than ever.

A few decades ago, if you wanted to learn a martial art, you had to find a good instructor and go to their class to learn.

Now you can just search for techniques on YouTube. There are thousands of world class tutorials at your finger tips:

Even though there has never been more information available on jiu-jitsu, the people who get good at jiu-jitsu the fastest are not the ones who watch the most videos.

In fact, I was in a class before and someone excitedly mentioned they had downloaded a new video series only to be met with chuckles by the more experienced practitioners.

”I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.”

— Bruce Lee

Watching videos can be useful insofar as they show you what’s possible and the general direction you want to take things in a fight.

But to think you can use disembodied knowledge to beat an opponent in a martial who has embodied knowledge is a ludicrous idea.

Yet, many of us believe that simply by reading books, we will be a much more formidable opponent against life.

Seneca provides a great warning on the danger of overloading on books, read the quote in full:

”Be careful, however, that there is no element of discursiveness and desultoriness about this reading you refer to, this reading of many different authors and books of every description. You should be extending your stay among writers whose genius is unquestionable, deriving constant nourishment from them if you wish to gain anything from your reading that will find a lasting place in your mind. To be everywhere is to be nowhere. People who spend their whole life traveling abroad end up having plenty of places where they can find hospitality but no real friendships. The same must needs be the case with people who never set about acquiring an intimate acquaintanceship with any one great writer, but skip from one to another, paying flying visits to them all. Food that is vomited up as soon as it is eaten is not assimilated into the body and does not do one any good; nothing hinders a cure so much as frequent changes of treatment; a wound will not heal over if it is being made the subject of experiments with different ointments; a plant which is frequently moved never grows strong. Nothing is so useful that it can be of any service in the mere passing. A multitude of books only gets in one’s way. So if you are unable to read all the books in your possession, you have enough when you have all the books you are able to read. And if you say, ‘But I feel like opening different books at different times’, my answer will be this: tasting one dish after another is the sign of a fussy stomach, and where the foods are dissimilar and diverse in range they lead to contamination of the system, not nutrition. So always read well-tried authors, and if at any moment you find yourself wanting a change from a particular author, go back to ones you have read before.”

If we want to read to become wiser, it is wise to reader just a few books and “drill them” by doing something like:

Reading / allowing book to inform your perception / re-read / practice / re-read / talk about book contents / re-read extracts deeply / take a break from material / re-read / etc.

This is definitely not the typical way we read books. But this is certainly the way that self-improvement used to be read.

At one point, before the invention of the printing press, books were sacred items. If you got your hands on a good one, you would aim to commit a lot of the book to memory incase you lost it.

The word philosophy can be translated as “love of wisdom.” But it’s easy to confuse “true wisdom” with “information from wise people.”

The Thai forrest monk Ajahn Chah explains it well:

”The value of Dhamma isn’t to be found in books. Those are just the external appearances of Dhamma; they’re not the realization of Dhamma as a personal experience. If you realize the Dhamma, you realize your own mind. You see the truth there. When the truth becomes apparent it cuts off the stream of delusion.”

Notebook Knowledge

Do you take notes when reading? Do you have a list of favorite quotes that you spout out during parties? Is your mind full of other people’s ideas and thoughts than your own?

Seneca warned us this approach:

”For it is disgraceful even for an old man, or one who has sighted old age, to have a note-book knowledge. “This is what Zeno said.” But what have you yourself said? “This is the opinion of Cleanthes.” But what is your own opinion? How long shall you march under another man’s orders? Take command, and utter some word which posterity will remember. Put forth something from your own stock. For this reason I hold that there is nothing of eminence in all such men as these, who never create anything themselves, but always lurk in the shadow of others, playing the rôle of interpreters, never daring to put once into practice what they have been so long in learning. They have exercised their memories on other men’s material. But it is one thing to remember, another to know.”

If you want to memorize maxims from your favorite thinkers, that’s fine, but never at the cost of your own contributions.

What maxims have you created? What arguments are you grappling with? What connections are you making between knowledge that you haven’t heard of before? What great minds do you disagree with? What experiments have you ran? Are you a teacher or just a student?

Going back to the analogy of jiu-jitsu, when you reach a black belt level (usually after 10-15 years of study and gruelling sparring), you are now a professor. You can award other people belts. And you have your own form of jiu-jitsu that you can teach to others.

Here is a sample of the most popular jiu-jitsu tutorial DVDs. Each of these teachers learned the fundamentals, practiced their art, and are now teaching their way of doing things. They are not constantly quoting other practitioners. Their lessons came from their experience.

This is the natural form of progression that all great practitioners go through, from musicians to artists to athletes and beyond. First they look to others in their field to learn from them, then they practice, then they come up with their own formula for greatness.

We must be careful when it comes to reading that we don’t get stuck on the first part of the process—consumption.

8 Reading Rules

In this post, I’ve outlined some of the issues with reading lists, speedreading, and viewing books as a goal. But now I want to switch the focus to best reading practices.

1. Read at Whim

Listen to your intuition for what to read next. Stop reading books you’re not enjoying. Don’t follow a reading list if your heart is not in it. Think of reading as an adventure, and travel to places that interest you at whim.

2. Make Re-reading a Habit

10% of the books you read every year ought to be books you’ve already read. Think of these as sacred documents that could be read hundreds of times before they’re fully understood.

3. Talk About What You Read

When it comes to jiu-jitsu, you have to drill the technique you learn with a partner before you can say you “know” it. When it comes to reading, talking about what you learn is one of the best ways to integrate the knowledge.

4. Argue and Converse With Authors

If you’re reading properly there should be many authors you disagree with. When you’re reading, you should see the exchange as an interaction where you are questioning the author and then imagining their responses.

5. Write Something You Can Read

Don’t just fill your head with other people’s thoughts. Think of books as teaching you the way the pieces on a chessboard move. Writing and creating is playing the game. Learning to play chess without ever playing chess is a waste of potential.

6. Create Your Own Reading List

There’s nothing wrong with looking at reading lists for inspiration, but if you follow the “read at whim” rule, you’ll want to create your own reading list that is uniquely your own.

7. Read Deeply

Don’t rush through books only to check them off your list. Read slowly and deeply. Savor each sentence.

8. Read Books for Entertainment

Don’t get caught in this trap of only seeing books as this means of “improve yourself.” Read things that entertain you, that excite you, that make you laugh or cry. Read comics. Read things that you wouldn’t want other people knowing about!

Jon Brooks

Jon Brooks is a Stoicism teacher and, crucially, practitioner. His Stoic meditations have accumulated thousands of listens, and he has created his own Stoic training program for modern-day Stoics.